Thoreau’s Ethics of Delight

I have been thinking about what Henry David Thoreau, a man so often described as “saint of the woods,” would make of us. He’s been a kind of companion to me through the last seven years, and I hear him sometimes—in an interior wordless way—puzzled and delighted and enraged by various features of contemporary life. My new book, Thoreau’s Religion: Walden Woods, Social Justice, and the Politics of Asceticism, tries to explain what caught my interest in thinking about his significance now. The asceticism Thoreau portrays in Walden, his life of simplicity in the woods, is guided as much by hope for a just economy as it is grounded in private contemplation of nature. In fact, Thoreau thought, the pursuit of a just economy on the one hand and nature piety on the other were both oriented toward one end: spiritual flourishing for an integrated whole, which would entail justice for all, including all humans as themselves a part of nature.

Walden’s twentieth-century reception would not lead you to this conclusion easily. In general, Thoreau’s thought has come down through two streams, both of which often took him to be areligious. One stream came through readings of Walden that generally focused on Thoreau’s nature piety. Another came through Thoreau’s “political writings” and their centrality to twentieth-century political thought. But these streams can and should be integrated, offering a reading of Walden that describes Thoreau’s ascetic practice in the woods as drawing on religious traditions and itself a form of politics that was religiously motivated.

Many have taken Thoreau’s asceticism to be a kind of stern, lonely, puritanism—religious, yes, but maybe in a bad way. They have in mind places where he recommends, for example, “a stern and more than Spartan simplicity of life” (II, 17). They take him to have withdrawn from important social and political bonds that ought not be renounced, indeed that are required for a just political life to succeed.

In response to this, I interpret the asceticism of Thoreau’s Walden as offering an ethics of delight that was specifically directed against the problems his critics have taken him to enact. Thoreau began the book worried that others in Concord practiced too stern an asceticism. “I have travelled a good deal in Concord; and everywhere, in shops, and offices, and fields, the inhabitants have appeared to me to be doing penance in a thousand remarkable ways” (I, 3). Their economic practices were bad for them, Thoreau thought. “The laboring man,” he wrote, “has no time to be anything but a machine” (I, 6). It was in this economic sense that he famously wrote that they were living “lives of quiet desperation” (I, 9). He wrote the book in an attempt to make imaginable a gentler way of life.

Walden aimed to describe a mode of living that could ease the economic burden Thoreau saw all around him in Concord, that could give people time that they could live instead of “spend.” He had suggested that it was “ignorance” that made men live like this, but he went on to express a surprising tenderness toward these folks whose lives he described. Before we judge the desperate, laboring man he had just called ignorant, Thoreau wrote, “We should feed and clothe him gratuitously sometimes, and recruit him with our cordials” (I, 6). In order for our best qualities to find a home in society, Thoreau thought, we have to treat ourselves and one another “tenderly.” He wrote, “The finest qualities of our nature, like the bloom on fruits, can be preserved only by the most delicate handling. Yet we do not treat ourselves nor one another thus tenderly” (I, 6).

The asceticism I describe in Thoreau’s Religion is of this tender kind. It refers not only to the things that Thoreau gave up, but also to what he gave those things up for, the positive practices he pursued in the woods: hospitality, housework and other labor, bathing, reading, writing, sitting, rowing, fishing, looking, walking, flute-playing, keeping appointments with trees, gossiping, visiting neighbors, and bean-hoeing, among other things. These were practices that “the mass of men,” in their desperation, could not find time to do, and Walden hoped for—and attempted to enact—a better future for all of us.

In his thinking about asceticism as a positive practice that is intended to protect our finest qualities like the bloom on fruits, and to teach us to treat ourselves and one another more tenderly, I also find Thoreau in what may seem an unlikely alliance with some contemporary voices advocating tenderness and joy as political ambitions.

Take, for example, The Nap Ministry, a project created by Tricia Hersey that is part installation art, part womanist theology, part abolitionist activism. The motto of the project is “rest as resistance,” and Hersey—the Nap Bishop—tweets regularly about how sleep and other forms of rest are essential to liberation: “Perfectionism is a function of white supremacy. You can lay down.” Hersey specifically views “grind culture” (her name for contemporary forms of stern economic culture) as intrinsic to racialized capitalism. In an interview with Patrisse Cullors and Autumn Breon Williams, Hersey explains, “It’s the thing that started when our ancestors were on plantations—the culture of seeing human beings as machines. The word ‘grind’—when you think about gears and grinding on a machine—it sees our bodies and who we are as just being machines for production . . . and everything about rest has been distorted because of that.” Hersey’s nap installations aim to preach the good news that sleep is not a privilege, but a divine right. Hersey herself is currently on a two-month “sabbath,” stepping back from her public work until May 1.

Hersey’s work draws on a long tradition of Black feminist thought and activism, which is proliferating in our time. The book Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, by adriane maree brown, offers a “politics of healing and happiness,” set against a vision of contemporary activism as itself a kind of grind work. Her vision draws on Black feminism to imagine how social justice should feel good. Bahia Ahad-Legardy’s forthcoming study Afro-Nostalgia: Feeling Good in Contemporary Black Culture, uncovers “an archive of black historical joy” that attempts to counteract predominant narratives of Black trauma and oppression as a resource for “a more affirming and hopeful future.”

The point of setting these examples in conversation with Thoreau is not to suggest that they are indebted to him—they may or may not be—but to improve our understanding of Thoreau, to draw him back into the world where we live, and to let him teach us, as Walden tried so hard to do, that the work of building a just world depends on our finding and cultivating tenderness toward ourselves and one another.

#

Alda Balthrop-Lewis is a Research Fellow in the Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry at Australian Catholic University. She holds a PhD in Religion from Princeton University and has taught Religious Studies at Brown University. Her research, which focuses on religious ethics and the circulation of ideas among theological, artistic, and popular idioms, has appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion and the Journal of Religious Ethics. Her first book, Thoreau’s Religion, came out in January, in New Studies in Religion and Critical Thought at Cambridge University Press.

This Counterpoint blog may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 17 March 2021.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

This essay was first posted at Sightings, a project of The University of Chicago Divinity School.

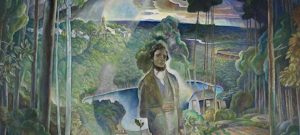

Photo Credit: “Walden Pond Revisited,” N.C. Wyeth, ca.1932 (courtesy of Brandywine River Museum of Art).

1 Comment

At the End of the World (in a Van) – Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge · March 24, 2021 at 9:00 AM

[…] aimless drifting, back in the 1850’s—and Thoreau’s religious asceticism and self-reliance (so wonderfully discussed here by Alda Balthrop-Lewis) ghosts several moments in Nomadland. In one brief scene, Fern is seen […]