Calling All Solarpunks! Symmetrical Myths and Rituals for Survival

We are living in a moment where progress is no longer forward, but on we trudge down that doomed path. The “end of history” promise is of a globalized world as the ultimate social and economic antidote, but our planet simply cannot regenerate fast enough to keep up with this notion of “progress.” As a result, several reactions have occurred due to planetary failures in 2021. The first is a neo-conservative turn that is nationalistic and clings to a false past (a common reaction throughout history in urgent times). The second involves tech-billionaires proposing orthogenetic evolution where we bliss-off Earth, a notion no way based in reality and just the colonial modernizing front in new clothing, or as Donna Haraway calls it, “white, male, phallic, masturbation” (Haraway, 2020, 32:00). Yet another is an archaized “return to nature” narrative, which acts as if globalization has not occurred or is not on-going and further enforces human exceptionalism to the rest of the natural world (Bauman, 220). And finally, the idea that it is too late—it is too strong, and we are too weak (Haraway, 23). These options are not viable or productive, as all are just as much a fairy-tale as Fukuyama proposing that Western globalization would be the end of history. This is why nurturing alternative, attractive futures that provide (partial) healing are absolutely paramount.

Artists have the unique capacity to do just that. Terence McKenna argues that language, or storytelling through art pieces (whether poetic or aesthetic), will be the battleground for our future when “we don’t have centuries of gently unfolding time ahead of us” (McKenna, 1990, 40:18). The artist, as mystical journeyer and subsequent shaper of matter thrives in moments of disequilibrium in order to shape all things, including consciousness, to novel forms of connectedness through material interactions. Artists engage in materialist practices in the present that can create futures and communicate those visions beyond the “usual mouth movements mediated by ignorance and hate” (McKenna, 1990, 42:10). Enter Solarpunk, a little-known movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that imagines technological, sustainable, and equitable solutions at a local level. It does not deny technological advancements as an important and necessary ally in nurturing a sustainable future. It also does not rely solely on a “techno-fix” to, as Haraway says, “save God’s naughty but clever children” (Haraway, 22). Solarpunk is not blindly optimistic in the sense that it envisions a world that is unaffected by climate destruction, as numerous ecosystems have already gone extinct (this is what is meant by “partial” healing). Solarpunk seeks to answer the question, “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?” (Springett, 2019, 10:20). Jay Springett explains that, “as our world roils with calamity, we need . . . [solutions] to live comfortably without fossil fuels, to equitably manage scarcity and share abundance, to be kinder to each other and the planet we share. At once, a vision of the future, a thoughtful provocation, and an achievable lifestyle” (Springett, 2017). What is so punk, you ask, about a movement that may appear to some a quixotic hippie fantasy? In a world that treats climate destruction as inevitable, solarpunk might be the most punk movement of all. There is an element of the Gil Scott-Heron, “the revolution will not be televised,” at play here (Heron, 1971). The Sex Pistols reacting to the climate in Britain in the late 1970s, an image of leather, material excess, consumerism and individualism, is no longer punk as it closely resembles the master narrative. As Jay Springett explains: “fighting for things we want to see in the world against the master narrative is punk as hell” (Springett, 2019, 13:35).

Imaginal spaces create pockets of structure in our lived realities and temporalities; in other words, ideas shape matter. In the West, we tend to see performance as fake, but one who studies religion will know differently. Rituals, rife with symbols, usually accompany and are the embodiment of powerful myths. Cosplaying solarpunk as a form of ritual includes growing organic food in your yard, composting, guerilla gardening, permaculture, and supporting decentralized infrastructures (such as wind or solar energy), all as places of resistance (aka, punk as hell). Solarpunk stories are not just fiction, they are theories in themselves and these stories provide an alternative philosophy to work out new thoughts and stories to live by.

Shweta Taneja’s “The Songs that Humanity Lost Reluctantly to Dolphins” presents a solarpunk version of the Pied Piper, where all the human children toddle down to the seas after hearing the song of dolphins, all forms of life joining in as accompaniment, the children never to be seen again (Taneja, 284–293). Human adults are unable to be captured by this song in the same way their children are (the effect of the song being called “empathology”) (Taneja, 288). After years of fighting and even waging war on dolphins, the human adults finally acquiesce and humble themselves in the face of other members of the planetary community, and the human children return. It is a story that demonstrates empathy as a rebellious youth movement in itself, and demonstrates the necessity of multi-species environmental justice by expanding the range of actors to include the nonhuman. Bruno Latour argues that nonhumans (things and beings) must be lifted from that of object to subject in order to dismantle modernity (Latour, 13, 59); this object/subject divide is imaginative as we are entirely dependent on our planetary community for survival. So, storytelling provides the perfect avenue for the nonhuman and human worlds to reconnect in our imaginations.

Another solarpunk story that looks to nurture a future that does not resemble the Anthropocene is Caroline Meyers’ “Solar Child” (Meyers, 185–194). This is a story that portrays a world where humans can photosynthesize through symbiosis with other organisms. It describes a world where, through embracing our reliance on other species, humanity can forego its need for centralized energy infrastructures as a more sustainable means for consumption and production. Zoological sciences are increasingly finding that nothing is truly autopoietic (Gilbert, 325–41), or self-organizing, but rather sympoietic, meaning worlding-with and evolving-with in company (Haraway, 52–55, 70–120). Our world is sympoietic but the stories we tell ourselves do not reflect this reality. Neither “Solar Child” nor “The Songs that Humanity Lost Reluctantly to Dolphins” relies on any technologies of modern certainties, whether that be individualism, isolated agencies, chronological fossil-fueled time, or human exceptionalism (Bauman, 1–10). These are not monomyths and there are no primary heroes: the shift is very much from “me” to “we.” Other examples include stories such as Joseph F. Nacino’s “Mariposa Awakening,” which shows the mycorrhizal networks of mangrove trees working symmetrically with human beings to protect cities in 2071 against rising sea levels (Nacino, 145–158). The anthropos is not the only viable agent in these stories, and our survival depends on this knowledge. As a scholar of religion, I am curious about how stories shape our reality. From human dominion in Genesis to the Anthropocene, these are powerful myths that share the general message that humanity is at center stage. By making our strong stories weaker and our weak stories stronger, and then ritualizing those stories, we might engage in a materialist practice that creates symmetry between the human and nonhuman. The artist has the facilities to follow the thread out of the labyrinth that is human exceptionalism, where if we stay we will face our extinction. In other words, this is a rallying cry for all the true punks out there—unite and create to weaken the master narrative!

#

Morgan Tomalty is a scholar of religion with Queen’s University and the University of Toronto who focuses on storytelling and ritual and is interested in finding more ecological stories to live by. She is reachable at [email protected].

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 6 October 2021.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

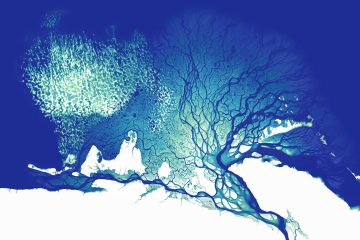

Photo credit: “2021’s Punk Scene?” © Morgan Tomalty, 2021.

1 Comment

Kolbeinn Höskuldsson · November 30, 2022 at 1:46 PM

http://www.animalinternet.earth