A Monarch Jeremiad

“Most of all, I shall remember the monarchs.”

—Rachel Carson, letter to Dorothy Freeman, September 10, 1963

In the summer of 2021, my family bid farewell to our longtime home in Indiana. We gathered clothing and provisions sufficient to last us several days on the road, loaded up a sad-eyed dog and two wary cats, and pointed the car westward toward California. To orient myself in this new land, I studied the songs of unfamiliar birds and learned to recognize other alien forms—an endless parade of flowering plants, a profusion of strange, comical succulents. Accustomed to the regularity of four seasons, I searched for patterns in the changing landscape, seasonal rhythms to anchor the passing year.

In autumn, tiny White-crowned Sparrows swept in from the north and whistled, unseen, in the dense foliage of Cape Honeysuckle. Winter rains came, and a band of rubbery green shrubs—Jade, I learned—responded with tiny star-shaped blooms, just in time for Christmas. Citrus bent toward the earth, waterlogged, while agave sprouted mysterious elephant trunks, seemingly overnight. In spring, a sprawling, woody vine that I had taken for a weed suddenly exploded in clusters of pink blossoms that exhaled a heady perfume. Jasmine, locals informed me.

“There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature,” Rachel Carson writes, “the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.” Climate change is now scrambling many traditional markers of seasonal change, leaving us anxious and disoriented.

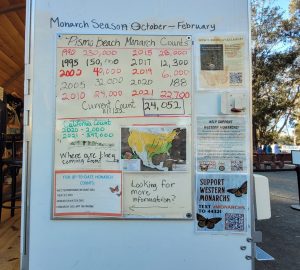

Monarch butterflies are one such harbinger of cyclical return. Their migration has punctuated meaningful seasons and difficult journeys in my own life. My newly-adopted town of Goleta, in southern Santa Barbara County, is home to one of California’s largest overwintering roosts. The monarch’s return to such sites is greeted with Thanksgiving Day butterfly counts (like Christmas Day bird counts) and a variety of celebrations. But sometimes, lately, they don’t return.

Across many cultures, butterflies are seen as avatars of the soul, and associations of butterflies with returning spirits of the dead are especially strong in the case of monarchs. Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead), a 3000-year-old tradition originating in central Mexico, occurs at the beginning of November, when monarch migration has traditionally peaked. In festivals and parades honoring the dead, participants dress in monarch costumes. Papier-mâché skeletons are fitted with bright monarch wings.

Monarchs’ arduous and precarious migrations inspire hope and perseverance. Their strange metamorphosis—the birth of a new winged creature from the imprisoning crucible of the chrysalis— symbolizes resurrection, and continuity in the midst of radical change.

Humans have long depended on monarchs to make sense of death, to process loss and change. What happens when a symbol of hope and continuity becomes a symbol of loss? When a creature emblematic of nature’s own powers of resurrection and renewal succumbs forever to extinction?

Monarchs are often divided into two populations. Eastern monarchs, which account for roughly 99% of all monarchs in North America, can travel up to 3000 miles to overwinter in high elevation mountaintops in central Mexico. Their summertime breeding range covers much of the US and parts of southern Canada east of the Rocky Mountains. The considerably smaller population of western monarchs breeds west of the Rockies, overwintering in forested groves at numerous sites along the California Coast and Baja. While attention is often focused on eastern monarchs whose epic journey inspires awe and delight, both populations have seen steep declines in recent decades.

The exact causes of monarchs’ decline—and their occasional, happy rebound—remain somewhat obscure. Loss of breeding habitat, widespread use of pesticides, and the decline of monarchs’ host plant, milkweed, are all implicated, although the lines of causation are complex and sometimes disputed. In the years immediately preceding my arrival in California, monarchs had an especially poor showing on the West Coast. Those years also saw periods of severe drought and the outbreak of catastrophic wildfires. It stands to reason that climate change is a major driver of monarch extinction.

Annual surveys recorded a precipitous drop to only 2000 western monarchs on the central and southern coast of California in the winter of 2020–2021. For coastal towns like mine, monarchs are integral to the community’s identity. “Goleta” in Spanish means schooner, a nod to the area’s rich maritime history when the Goleta slough served as a refuge for ships during wet winter months. Images of schooners are common around town, but when Goleta was officially incorporated in 2002, the symbol chosen for the city’s seal was a familiar orange-and-black butterfly drifting above rows of agricultural fields and stylized ocean waves.

Other small towns dotting the coast claim the distinction of “Butterfly Town, USA.” In 2021, not a single monarch returned to Pacific Grove, California, and only one was counted in 2022. The monarch is the city’s logo. Motels and cafes pay homage to the butterfly, and an annual parade in October, where children dressed as butterflies welcome the monarchs, has commemorated their seasonal arrival since 1939.

What would it mean to be a butterfly town with no butterflies?

In a letter penned in 1963, Rachel Carson recounted a recent outing where she and her companion, Dorothy Freeman, had witnessed migrating monarchs. Diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer and nearing the end of her life, Carson found enormous meaning and comfort in the scene, which she replayed for Dorothy:

We talked a little about their migration, their life history. Did they return? We thought not; for most, at least, this was the closing journey of their lives. But . . . we had felt no sadness when we spoke of the fact that there would be no return. And rightly—for when any living thing has come to the end of its life we accept that end as natural. For the monarch, that cycle is measured in a known span of months. For ourselves, the measure is something else, the span of which we cannot know. But the thought is the same: when that intangible cycle has run its course it is a natural and not unhappy thing that a life comes to an end.

The “not unhappy” cycle that runs its course is that of the individual migrating creature. It is not the cycle of life itself. Carson would have found no comfort in witnessing this closing journey had she considered the possibility—which we must now confront—that the monarch procession as a whole might be halted forever by extinction.

Environmental philosopher Holmes Rolston describes extinction as a “superkilling” that terminates not just individual lives, but the species line, and the very process of speciation. Extinction “kills essences beyond existences, the soul as well as the body . . . birth as well as death.”

In January 2008, with Rolston as my climbing companion, I hiked 10,000 feet to reach the monarch roosting site at El Rosario Sanctuary in Michoacán, Mexico. Later, he sent me his account of our pilgrimage, describing thousands of butterflies “mostly hanging off the branches of oyamel firs (Abies religiosa … religiosa comes from the tip of the branch forming a cross).” Rolston estimated the number of monarchs clustered on the sacred firs to be around 100,000. He wrote of a “central mystery” at the heart of the spectacle:

The butterfly that goes from Canada to Mexico and partway back lives six to nine months, but when it mates and lays eggs, it may have gotten only as far as Texas, and breeding butterflies live only about six weeks. So a daughter born on a Texas prairie goes on to lay an egg in South Dakota that becomes a granddaughter. That leads to a great-granddaughter born in Canada. In autumn, how does she find her way back to the same grove in Mexico that sheltered her great-grandmother?

The mystery continues to elude us. Monarchs may disappear before we can even begin to grasp it.

With the closing of the 2023–2024 overwintering season, scientists now estimate a 59% decline in the eastern monarch from the previous year, the second-lowest level ever recorded. We are witnessing a superkilling. The casualties reach beyond the unthinkable tragedy of monarch death to touch our own humanity: we will see the diminishment of our capacities to make sense and meaning of the world, to orient ourselves in cycles of seasonal change and return, of life and death. Our interdependence with monarchs is profound and our recognition of it may come too late.

#

Lisa H. Sideris is Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, with affiliation in the Department of Religious Studies. Her research focuses on the ethical significance of nature and natural processes, and how environmental values are captured or obscured by narratives in religion and the sciences.

Lisa H. Sideris is Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, with affiliation in the Department of Religious Studies. Her research focuses on the ethical significance of nature and natural processes, and how environmental values are captured or obscured by narratives in religion and the sciences.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge on 6 March 2024.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

Image credits: All images © Lisa H. Sideris, 2024.