Spirituality in Forest Management—A New Orientation in Human-Forest Interactions

By Cathrien de Pater

The hall is crowded. The community of Rhenen (in the Netherlands) has gathered to question why so many trees were cut in the nearby woodlands over the last year. The foresters explain the necessity of thinning for biodiversity, sharing their knowledge and their sympathy with the audience, but tension continues to run through the room. Although this meeting is a far cry from the violent confrontations in other, faraway forests, I sense the same emotional undercurrents. Dutch citizens grieve about global forest loss—epitomized by the recent burning of Australian and Brazilian forests—and this resonates with what happens in their own country. Among the foresters, these feelings also go deep. I found that out years ago when I interviewed foresters about why they chose forestry as their profession. Foresters disliked the term “spiritual,” but what drove them and kept them going was a deep reverence for the earth and the cosmos, a profound connection with nature, and a strong ethic of responsibility for the green world. The deepest core of forestry is spirituality.

Spirituality has also entered the forestry domain via other avenues. Indigenous people have been increasingly successful in gaining recognition of their socio-cultural needs in the international policy arena. As a result, all major forest-related global fora include “cultural and spiritual values” in their policies and strategies, from biodiversity and forest certification to climate change. However, despite this global recognition of spiritual values as criteria for sustainable forest management, there is only scattered evidence that these values are operationalized in practice, and if they are, the question is how. How is spirituality articulated in the practice of forest management? What does that mean for the forest and the people concerned?

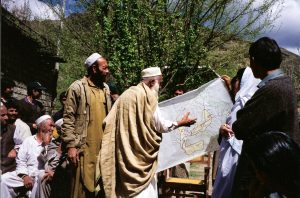

Since the “people turn” in scientific forestry in the late 1970s, local and Indigenous people’s rights and livelihoods have gradually formed the core around which field forestry cooperation has developed. With ups and downs, foresters have learned to work with these social dimensions. Concepts such as “community and social forestry” have developed, with more or less lasting success. I worked on this in Nepal in the early 1980s and observed a greener country in the 1990s, after favorable policy changes. At the time, we didn’t explicitly deal with spirituality. Only later, while working in Northwest Pakistan, did I realize that the spiritual dimension might be important. Foresters of the Malakand Social Forestry project issued booklets to villagers with Islamic injunctions encouraging tree planting and environmental care. Combined with a thoughtful and culturally sensitive approach, this motivated villagers to come together to reforest denuded hillsides. After the project ended, villagers continued to keep the hillsides green. These examples raise additional questions: Should foresters use spirituality as a motivational tool in their work with communities? And how does that relate to questions of power?

“Forest management”—human activities in forest ecosystems which are intended to achieve objectives with regard to the use and conservation of a specific forested area—was traditionally aimed at the perpetuity of the forest, mainly focusing on its productivity; when attention to biodiversity and social functions increased, the key term became “sustainable forest management,” defined by the UN as aiming “to maintain and enhance the economic, social and environmental values of all types of forests, for the benefit of present and future generations.”

Sustainable forest management is implemented by forest managers—that is, all the human beings who have a direct influence on the management of a forest, be they professionals or community members. Forest managers rarely work alone. They are in dialogue with an increasing number of parties (“stakeholders”) about management interventions. Indications are that these parties are increasingly opening up to “the spiritual,” or are at least less reluctant to mention spirituality in technical discourse than they were before. We see this worldwide. First Nations in Canada, for instance, are increasingly articulating spiritual values in forest management. In Europe, the public is increasingly asking for nature retreats, tranquility, scenic beauty, balanced energetic forces, or natural burials. How do forest managers cope with this “spiritual” demand, and how does it affect their management?

The nexus where higher-level policies and practices come together is the “forest management plan” (FMP). FMPs are a crucial element of forest management in many parts of the world. They are created in various ways, from “top-down” to community-based processes. FMPs are geographically and temporally demarcated, and they contain knowledge, rules, and discussions. Spiritual values may be expressed in FMPs in various ways—in wording, emphasis, and prescriptions, implicitly or explicitly. However, forest managers don’t always follow forest management plans precisely. Therefore, we should ask: What kinds of spiritual values are expressed in forest management plans and practices? How “concretely” are they operationalized?

In order to study spirituality in forest management, it helps to distinguish the following dimensions: (1) experiential-emotional (subdivided into aesthetic, relational, restorational, and “life force” dimensions); (2) practical-ritual; (3) mythical-narrative; (4) philosophical; (5) ethical; (6) social-institutional; and (7) material. I’ve investigated the occurrence of these dimensions at various levels of operational detail in twenty FMPs from the Netherlands and Canada. It appears that spirituality, especially its experiential dimensions, is indeed an undercurrent of forest management in many forms. It even surfaces at times, especially where First Nations have a major say in the formulation of FMPs. These findings are still preliminary and should of course be field-checked.

So will spirituality become genuinely influential in forest management? It will take time; economic and ecological factors will likely remain dominant when it comes to planning. But Dutch forest owners are increasingly serious in articulating the “experience of nature” in their FMPs. First Nations have delineated sacred areas and started cultural education programs. All of this still falls within the scientific management paradigm. Another possibility is the revision of the paradigm itself. A first sign of this is the emergence of “spiritual governance” in discourse on the management of sacred natural sites: granting agency to non-human or even non-material entities is part of this process. With all of its “pros and cons,” this could be an interesting perspective for forest management, too.

#

Catharina de Pater studied tropical forestry in Wageningen and interreligious spirituality in Nijmegen (the Netherlands). For 30 years she has worked as a forestry adviser with the United Nations (FAO) and the government of the Netherlands in the development of community and social forestry, international cooperation, biodiversity, and communication. She has worked extensively in Asia, Latin America, and Europe. In the last 20 years, she has specialized in the up-and-coming academic field of nature and religion, with a focus on forests. Her current occupation is a PhD project on spiritual values and forest management with the Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group at Wageningen University and Research.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 7 April 2020.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

Photo credit: “Malakand Social Forestry Project in Pakistan” – © Cathrien de Pater 2020