Inside Out / Outside In: Returning our Bodies to the Commons

Often times the “work” of overcoming what Bruno Latour called “the great divide” between humans and the rest of the natural world is focused on externally relating to the rest of the natural world of which we are a part. We focus more on right actions: what we can do to save the planet or lead a more gentle, environmentally friendly and just way of life. Through going out to be in nature, thinking about our ecological footprint, and taking part in environmental actions and activism, we might better recognize our entanglement (ecologically and evolutionarily) with the rest of life on the planet. We will call this working from the outside in. If we find a way to “re-enchant” the world through some sort of spirituality of nature and/or overcome our nature deficit disorder, we might more “authentically” re-attune to the other earth bodies around us and that make us up. This is one important piece of addressing the problems that arise from anthropocentric ways of living in the world. But it does not always address the ways in which retreating to the internal work that needs to be done might be equally beneficial in terms of helping us to live at more of a planetary pace. We will call this working from the inside out.

Many postmodern academics (including myself) have spilled a lot of ink arguing for a non-essentialist understanding of the self, of humans, and in general. There are no essences or stable forms, there is no external aim or “telos” toward which we move. How, then, is it possible to reorient ourselves in relation to other selves when there is no essence or “correct” way to do so? What good does “internal” work do if there is no “authentic” self? This non-essentialist and non-teleological way of understanding reality has come under attack recently by some academics. In the face of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” in the face of the erosion of trust and authority of higher education, and in the face of the erosion of respect for expertise (in general), some are blaming the postmodern lefty types for fomenting this “anything goes” reality. While a naïve version of postmodernism is being utilized by right-leaning politicians and politics, it is a far cry from most complex and thoughtful deconstructive postmodern theories. Here, I want to suggest that something like “staying with the trouble” in an entangled, non-essentialist, non-teleological, and emergent planetary community might benefit from a turn inward that complements our commitments toward outward engagement. Dealing with things like eco-anxiety, the grief of species extinction, and the burn out of trying to meet our daily demands at the fossil-fueled pace in which many of us live our lives, has left little time for this turn inwards. Perhaps reflective practices that help us to focus on this non-essentialist and non-teleological reality may actually help us slow down, think together, and co-create planetary ethics based on concern for all bodies.

In many senses, this relational understanding of the world has affinity with a Buddhist ontology. There is no self, no permanence, and everything is shifting and changing. For a philosophy or outlook on life that is so non-essentialist, the practice of Buddhism entails much contemplation and quiet reflection, and certainly provides ethical guidelines. The focus of the Zen tea ceremony, for instance, is on how each movement ripples out to affect the whole. You only use a certain amount of tea, water, and fire in order to cause the least harm possible. If we all live at the expense of other life, this means paying deep attention to the life that enables us to live. Maybe we might begin to focus on our entanglement from the inside out.

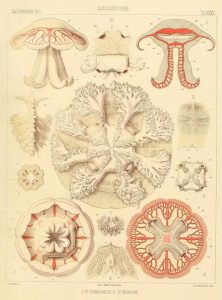

Every organism is an internalization of the ecosystems around them. Ernst Haeckel, for instance, coined the word “ecology” to suggest that the different environmental communities in which organisms emerged and interacted with as a part of, were responsible for the evolutionary differences and changes found amongst members of the same species in different places. Taking things a bit further, metaphorically, if we contemplate our own insides, we will begin to see our entanglement with all the other elements and organisms that have come before us. In addition to seeing “the universe in a grain of sand,” we can see ourselves and other bodies as different manifestations of the universe. This is of course no news to Taoists and Confucians, who have a sense of the “cosmic self:” i.e. that all things in the cosmos are interrelated. Deep reflections, meditation, tai chi, contemplation, prayer, pilgrimage, fasting, shamanic journeys, yoga, and many other rituals within religious and spiritual traditions, along with holistic medicine and healing practices, are all geared towards slowing down and “going in” to understand one’s entanglement with the rest of the world (past and present).

Even in modern and western science, which has focused mainly on productive and reductive technology transfer, we find many reasons to be more contemplative in a way that helps us understand our most inner selves are actually outer selves. Work being done on the microbiome, for instance, really drives home that our bodies are more like ecosystems, which change with the ecosystems around them, than they are isolated entities who enter in to meet other bodies that then make up the whole system. All living bodies are porous, they allow things to move in and out, creating the ongoing flow of life in different forms until the form of individual things break down and become life for new forms. Each entity is only “for a time,” and this is due to the ongoing, evolving, planetary community from which we emerge, and back with which we eventually merge.

Our tissues, fluids, and bones are made up of the other tissues, fluids, and bones. We derive energy ultimately from the sun, but as animals, we must use the “transformed sunlight” in the form of other bodies that we consume rather than directly consuming the sun. To reflect on the other bodies that make us up is to reflect on our connections to that wider ecosystem, planet, and cosmos. It is to reflect on all our bodies as made up of the same common elements of earth, air, fire, and water. What if we spent more time creating spaces and places in universities, religious communities, and public areas that enable us to have these collective and quiet reflections? If we can create fossil-fueled spaces and shopping malls, then, surely, we can create spaces that help us to recognize a posthuman world in which maybe our largest ethical question is not only, “what ought and can I do?” but also “how ought and can I do less?” Part of the beauty of slowing down, as many slow movements have shown, is that we are able to live at more of a planetary pace, which simply enables other lives to live.

#

Whitney A. Bauman is Professor of Religious Studies at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami, FL. He is also co-founder and co-director of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge. His areas of research interest fall under the theme of “religion, science, and globalization.” He is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship and a Humboldt Fellowship, and in 2022 won an award from FIU for Excellence in Research and Creative Activities. His publications include: Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethic (Columbia University Press 2014), and co-authored with Kevin O’Brien, Environmental Ethics and Uncertainty: Tackling Wicked Problems (Routledge 2019); 3rd edition of Grounding Religion: A Fieldguide to the Study of Religion and Ecology, co-edited with Kevin O’Brien and Richard Bohannon, (Routledge 2023). He is also the co-editor with Karen Bray and Heather Eaton of Earthly Things: Immanence, New Materialisms, and Planetary Thinking (Fordham University Press 2023). His next monograph is entitled, A Critical Planetary Romanticism: Literary and Scientific Origins of New Materialism (Columbia University Press, forthcoming 2025).

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 28 May 2025.” The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

Image credits: Ernst Haeckel, “Discomedusae: 1-8 Cannorhiza, 9-12 Versura,” 1879. Public Domain Image Archive.