Discussing Esotericism and Spirituality in Germany

[For the German version of this blog post, click here | Zur deutschen Version dieses Textes geht es hier entlang]

Today, the German public-service television broadcaster ZDF launched another episode of the show “13 Fragen” (“13 Questions”). This is a debate format in which two groups of three people each, placed on a playing field, try to convince the other group of their arguments. Whenever a possibility of agreement opens in the discussion, the participants take a step on the playing field toward each other. It’s a format that bucks the trend toward polarization and encourages the search for understanding and compromise. When the moderators asked me a few weeks ago whether I would like to participate in an episode on the controversial discussion about “esotericism and spirituality,” I saw this as a good opportunity to help critically nuance the public debate, which is particularly in Germany being conducted in an extremely polemical and emotional manner. So I agreed.

The “13 Questions” revolved around the core question of whether esotericism and spirituality are merely harmless elements of an individual attitude to the world (“Team 1”), or whether we are dealing here with a dangerous movement that has radical right-wing and anti-democratic potential (“Team 2”). It was clear that, in view of these options, I ended up with “Team 1.” What then happened in the discussion can be seen as emblematic of the formation of public opinion on esotericism and spirituality in Germany.

For more than 30 years, there has been professional scientific research on esotericism, which today is represented by international scientific associations, scholarly journals, handbooks, historical overviews, and academic study programs. In Germany, too, successful research programs were launched, for example on “Enlightenment and Esotericism,” and last year the large DFG research group “Alternative Rationalities and Esoteric Practices from a Global Perspective” started at the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Now, the astonishing thing is that the German public is not at all aware of any of this research. What dominates public opinion in Germany are positions that either ridicule esotericism and spirituality or classify them as “dangerous”; neither of these positions feels compelled to even bother to consider the academic research on the subject. Nevertheless, the “critics of esotericism” present themselves with the gesture of scientificity, eager to carry the torch of enlightenment into the darkness of superstition (I commented on this attitude elsewhere). Not surprisingly, then, although in our discussion at “13 Questions” I was the only scholar in the room, the rhetoric of scientific truth belonged entirely to “Team 2.”

Of course, there are different approaches in esotericism research, which have changed over the years in critical dialogue and have led to reorientations. And there are scholars—including myself—who are skeptical about the analytical power of the term “esotericism.” But researchers generally agree that esotericism has to do with knowledge claims that sometimes go against the prevailing religious or scientific knowledge. Historical analysis then shows how certain forms of knowledge are either accepted or marginalized in concrete social settings—and this is by no means a straightforward development, but rather a palimpsest of religious, philosophical, and scientific alternatives that keep popping up in changing situations.

The German scholar of religion, Burkhard Gladigow, called this the “concurrent alternatives” of European history of religion. Examples include the divine knowledge of a Hermes (“Hermeticism”) or an Odin, the teachings of legendary philosophers such as Zoroaster and Plato, or religious-philosophical alternatives that Europe encountered in the course of colonial expansion (here’s an update on his theory).

All these alternatives—and particularly the fascination with non-European knowledge cultures—have been part of “esotericism and spirituality” in Europe and North America since the nineteenth century. Groups such as the Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 by Helena P. Blavatsky and others, and the Anthroposophical Society (founded in 1912 by Rudolf Steiner), which grew out of theosophy, are important conduits when it comes to the enormous pluralization of the religious and ideological field in the twentieth century. The so-called “New Age” movement of the 1970s and 1980s built on this. More or less marginalized at the time, the views and practices referred to as “New Age” are mainstream today in Europe and North America. Hence, the “boom” of astrology, tarot, reincarnation doctrines, witchcraft, or magical rituals is by no means a brand-new phenomenon; it has a prehistory that can easily be reconstructed.

But instead of considering this religious-ideological diversity and taking a differentiated look at the large spectrum of esoteric and spiritual movements, the German public confines itself to calling esotericism “secret knowledge” and pointing out the supposed proximity of this body of thought to right-wing radical, anti-Semitic, and anti-democratic tendencies (a criticism of esotericism, by the way, that one hardly finds in other countries). German critics then take quotations from the huge work of Helena P. Blavatsky (1831–1891) or Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925) and lump them together with statements of homeopathic doctors and self-declared shamans on “anti-Covid demonstrations” or in the “Reichsbürger” milieu, subsequently transferring them to all other “esotericists,” from Wicca followers to astrologers and neopagans. From a historical or sociological point of view, the flaws of these constructions and the degree of argumentative simplification are incredible.

This is not to say that esotericism and spirituality offer no inspiration for people with anti-democratic, racist, or anti-Semitic convictions. There is good academic literature available on this. What is more, if one third of the German population is susceptible to anti-Semitic or racist stereotypes, it would be surprising if these prejudices were not also found in the esoteric milieu. However, to conclude that “esotericism as such” is the reason for such intolerant tendencies is not convincing.

The same applies to the claim that esotericism involves “secret knowledge” that is only accessible to insiders, who then fall into an abusive dependency on the respective group leaders (“cult leaders,” “gurus”). Problematic group dynamics and criminal exploitative situations exist everywhere, from the Catholic Church to sports clubs, and the democratic legal system does well to prosecute such machinations and offer help to the victims. But the claim that esoteric or spiritual groups are structurally predisposed to such misconduct cannot be scientifically substantiated.

Germany and Western Europe today are characterized by a pluralization of beliefs and worldviews that is historically new. Trust in institutional forms of knowledge in religion, science, and politics is lower than in earlier periods; Christianity is in the process of being trimmed down from a hegemonic power to a “concurrent alternative” (and is resisting this with all its forces); in their search for identity and meaning, many people are experimenting with spiritual and philosophical offers that they find more convincing than those systems that can be regarded as the cause of the global crises we’re facing today.

There is no reason to criticize or ridicule this search for alternatives. A democratic society worthy of the name can tolerate ideological differences. The boundaries of what is acceptable are not drawn by a dominant social group or some opinion police, but by the rule of law.

What we need is an open and well-informed discussion that is critical of its own prejudices and projections, and that engages in listening to others rather than demonizing them in advance. This goal is one of the reasons why we founded Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge. Formats like “13 Questions” support such a search for understanding, and for that I am grateful to the moderators.

#

Kocku von Stuckrad is one of the co-founders and co-directors of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge. As a Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Groningen (Netherlands), he works on the cultural history of religion, science, and philosophy in Europe and North America. His most recent book is A Cultural History of the Soul: Europe and North America from 1870 to the Present (Columbia University Press). He lives in Berlin.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge on 31 May 2023.” The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

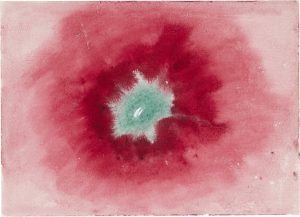

Photo credit: Hilma af Klint, Untitled, 1920. Photo by Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm, and the Guggenheim Museum. Downloaded from “Hilma af Klint: Beyond the Visible #2”. Hilma af Klint, the Swedish pioneer of abstract art, was part of the spiritual and theosophical milieu of the time and discussed her work with Rudolf Steiner.