A Watersheds Moment

By Gary Slater

The phrase “watershed moment” is used so commonly that it’s easy to forget how, if at all, actual watersheds come into it. If the metaphorical fit of watersheds with moments works well enough that the phrase has successfully become a cliché, there are nevertheless some awkward elements that emerge when one considers the idea more deeply. For one thing, the water within a given watershed flows into a common and relatively stable endpoint: although a specific stream or river will sometimes vary in its course, the endpoint itself, where the water flows into the ocean or some other endorheic body, typically remains unchanged. To associate the idea of a decisive shift with a single watershed makes less sense than to think of passing from one watershed to another, as with crossing over a continental divide. Better, then, to think of a “watersheds” moment, as in a plurality of watersheds representing multiple possible futures that shift when one moves in and out of them. In addition to foregrounding the plural, this way of thinking also focuses attention on the idea of boundaries as points that, like the edge of a watershed, turn one thing lastingly into another.

These elements—a multiplicity of watersheds, boundaries—are worth mentioning because of the illuminating role they play when the phrase “watershed moment” is applied to the time we are currently living through. The Jordan, Rio Grande, and Amazon watersheds, for example, are respectively known for their religious, political, and ecological importance. Yet for each of these rivers, all three categories are in fact imbricated in complex and causally-significant ways. To take just a single case, the Jordan River is revered by Muslims, Christians, and Jews as a symbol of receiving God’s promise. It is the place where (for Muslims) miracles were performed and several of the Prophet Muhammad’s companions buried, where (for Christians) Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, and where (for Jews) waters were parted as the Israelites crossed back into the promised land following the Babylonian exile.

Yet the Jordan’s significance is not exclusively religious: its deep interreligious background informs the political significance of the river today, situated uneasily as it is between the West Bank, the Kingdom of Jordan, southwestern Syria, and the State of Israel. The most visible consequence of this political friction is ecological, in that the river has become one of the world’s most contaminated waterways. Ironically, if religious relevance looms in the background of the political context in which the respective states fail to collaborate in maintaining the ecological integrity of the watershed, it also factors directly in the economic forces that have sought to maintain a portion of the river with immaculate cleanliness. This is the biblical site—Bethany Beyond the Jordan, or Al-Maghtas—where Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, a major destination for religious tourism.

From even this one example, the mutual interpenetration and enormous stakes of the religious, political, and planetary forces in our time is made visible, as is the importance of boundaries. Boundaries are increasingly prominent facts of the world. This is the case not just in terms of the ever-more-fortified borders that surround nation-states but also in the planetary boundaries that represent thresholds of destabilization for different subsystems within the overall Earth System. Boundaries function to create and reveal the sorts of religious-political-planetary intersections that define our time, both with respect to watersheds and beyond them. With respect to the Jordan, Rio Grande, and Amazon, for example, it is significant that each of these rivers constitutes an international border for some portion of its length, a fact that is causally significant for creating an intersection of the religious, political, and planetary.

Boundaries do not simply cause these intersections, however. They also reveal how distinctions that blend and merge in one way manifest in other distinctions that sharpen. Migrants seeking to cross from Mexico into the US, for example, camouflage their water bottles in dark colors to avoid detection on their journeys. Awaiting them are surveillance cameras, camouflaged as rocks or plants, that seek to detect migrants. In these opposing-yet-inextricable cases—migrants seeking to avoid detection, cameras seeking to detect migrants—the boundaries that distinguish human from more-than-human are blurred, even as the boundary that separates the citizen from the noncitizen is heightened. The former type of boundary is blurred, in fact, because the latter boundary is heightened, and the entire absurd situation would not exist in the first place without the constant, hulking presence of the international boundary line.

This observations exist within a rich academic context, as scholars have devoted increasing attention, in various ways, to religious-political-planetary interactions, including with respect to both boundaries and watersheds. Political philosopher Paulina Ochoa Espejo even attempts in her book, On Borders, to articulate a “watershed model” of borders as a replacement for the Westphalian “desert island model” of separate bounded territories. By reorienting political systems in line with watersheds, Ochoa Espejo argues, it is possible to mitigate the aspects of borders that divide and isolate and achieve not just more harmonious social relations, but also a better relationship with more-than-human nature.

Interpreting watersheds, especially rivers, in light of boundaries, and boundaries in light of watersheds, is a mutually beneficial approach for thinking creatively about religious-political-planetary interactions in our time. Thinking of boundaries—especially borders, which are boundaries’ comparatively concrete and politically-inflected counterpart—in terms of watersheds helps in two ways. First, rivers connect as well as separate, which is the same for borders as sites of both encounter and alienation. Second, like rivers, borders flow. Borders are dynamic, specific, and perspectival, by no means fixed, even if they remain stubbornly material in at least some aspects. Just as one cannot step in the same river twice, one also cannot cross the same border twice. Rivers therefore speak to the ambivalence of borders and their capacity to be reimagined.

As for thinking about watersheds in terms of boundaries, it has already been noted that boundaries both create and manifest intersections among religious, political, and planetary forces. What can be added here is that boundaries are especially helpful in preventing these intersections from being muddled to the point of sheer indistinction. In light of the enduring relevance of anchoring distinctions within each of the religious, political, and planetary as categories—evident in contemporary debates over the edges or limits of political membership, of religious traditions, and of the human—this suggests a vision not just for navigating among these key categories without falsely separating them, but also distinguishing better and worse forms of interaction.

#

Gary Slater is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Christian Social Sciences at the University of Münster and editor of the American Journal of Theology and Philosophy. His research is funded by the German Research Council (DFG), and it focuses on borders, migration, environmental ethics, interreligious theology, and philosophical pragmatism. The volume Ethics Across Borders: Reimagining Religious, Political, and Ecological Divides, which he co-edited with Lisa Landoe Hedrick, will be out with Routledge in December 2025.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 29 August 2025.” The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

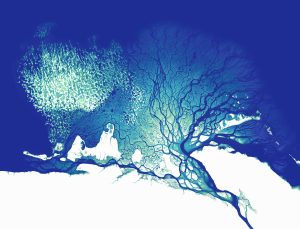

Photo credits: © Daniel Coe (Creative Commons license), with the image being of the Lena River Delta in Russia, derived from a high-resolution stereo digital elevation model. Free download from Flickr.