Ethics Without Transcendence: Criteria for Planetary Becoming

If we are going to have a radically immanent understanding of reality such as found in forms of new materialisms, among many other animist or pantheist ways of thinking, then we ought to begin to articulate how we navigate what counts as “better” or “good” when it comes to issues of knowledge production, ethics, and politics. My assumptions for this blog are that: a) humans and all things human are an emergent and evolving part of nature naturing; b) that there is no outside/objective point from which to judge and know; and c) that we thus can’t discern some sort of original essence, foundation, ideal form, or teleological final goal. If we build from these assumptions, then there is no knowledge for knowledge’s sake, but rather we must co-construct some guidelines for what counts as “good” knowledge and politics, or what is morally/ethically “good” or “better” than some other courses of action. What follows is my own attempt to create epistemological, political, and ethical guidelines for planetary thinking or what Latour might call living within the “critical zone,” or Haraway might call “staying with the trouble.”

The Humility of Humus

The etymological connection between human, humility, and humus (earth) is one that, I think, cannot be highlighted enough. There are, of course, many origin stories that have humans emerging from the dirt: Adam from the Adamah in the Torah, Qur’an, and Christian Bible; the fashioning of humans from clay in Greek, Egyptian, and Chinese origin stories; the many Indigenous stories that understand humans as being created from the clay or earth and that humans are “kin” with other life on the planet; and, of course, the scientific story of the evolution of life is one that suggests that life emerges from the oceans and then evolves out of the earth. The point is that the human is deeply tied to the earth in many religious, cultural, and scientific understandings of the origins of humanity. This is the first recognition needed for re-attuning to the evolving planetary communities.

Rather than act as if we are not of the humus, humility helps us to recognize that we are deeply connected to the dirt, the earth, and all life therein. Those knowledge systems and actions which promote this connection and deepen it, then, might lead to a “better” planetary future. In other words that which promotes our connection to the earth also promotes planetary truth, goodness, and beauty.

The Openness of Compassion

The knowledge of our entanglement with the humus, though not always a “good” or “beautiful” thing for the individual, may help open us toward more compassion. I would argue that there is some truth to the Buddhist understanding that life is suffering: everything lives at the expense of other life; our entanglement with the rest of the natural world means that we can be infected by viruses and bacteria, and that eventually our bodies will become food for other bodies. Our entanglement means that our relationships with humans and the rest of the natural world can harm and hurt, and that other humans and the rest of the natural world can be quite indifferent to our own needs. The etymology of the word compassion is “to suffer with.” And this is the second recognition needed for reattuning to the evolving planetary community around us.

I am not suggesting that we all become martyrs or suffering servants. Rather, I am saying that knowledge which opens our eyes to the suffering of other lives and opens our hearts to the pain of this suffering is knowledge that is good, true, and beautiful for the planetary community. This is not just the attention that the joys and pains of our daily lives call for, but also attention to the suffering caused by racism, sexism, ableism, heteronormativity, anthropocentrism, and many other institutionalized forms of violence in our worlds. The suffering caused by fossil-fueled climate change, by colonialism, and by hyper-extractive consumerism caused largely by the globalization of neo-liberal economic systems should not be something that we just think of as “life as usual.” To suffer with means to try to understand, and to stand with all those in the planetary community who are suffering in multiple ways, with an eye toward both witnessing that suffering and, when possible, alleviating that suffering by working toward worlds that are more truthful, good, and beautiful.

The Playfulness of Conversation

I think the prerequisites for developing something like a planetary polis, are the types of humility and compassion I have articulated above. What does it look like to have a real conversation? The etymology of conversation is something like “to turn together.” From my interpretation this means the ability to enter into dialogues with a willingness to be converted to others’ viewpoints. This type of conversation is at the heart of Hannah Arendt’s understanding of the political sphere. However, I would extend that sphere (which she does not) to the rest of the planetary community, the rest of the natural world. How might we be converted to ways of becoming that we learn from being in conversation with dolphins, whales, birds, primates, elephants, and other forms of animal and plant life? How might we hear the cries of species extinction, warming oceans, deforestation, and habitat loss in our efforts to “turn together” toward something “better”?

The ability to open oneself up to possible conversions in conversation with the entire planetary community is also a marker of what is true, beautiful, and good. Conversation stoppers and ideologies that do not entertain the knowledge and ideas of others are most often harmful. These open conversations are hard work, but there is also a sense of playfulness we might cultivate that helps, in the words of Nelle Morton, “hear others into speech.” The playfulness of song, poetry, creative non-fiction, speculative fiction, theater, and art (both human and non) may help us cultivate spaces that foster productive conversations: and these types of spaces are the spaces required for a planetary polis.

The Justice of Company

Finally with humility, compassion, and conversation, we might begin to develop more just ways of being together. The etymology of company, “with bread,” is simply the tradition of hospitality known as breaking bread together or eating a meal together. There is perhaps nothing more basic that humans (and non-human others) can do together. Of course, this is not always done in a just manner: some are impoverished while others indulge; the violence of factory farms and monocultures dependent upon pesticides and fertilizers and fossil fueled energy in general, cause much suffering and environmental destruction; the labor practices of those who enable a meal to be on a given table are unequal and often violent (depending on where one is). If we can approach our company with humility, compassion, and in a spirit of conversation, we might be able to better address these issues of justice (for humans, animals, and the rest of the natural world).

The more we create spaces for just communities, the more true, good, and beautiful the planetary community might become. This means creating spaces, and the infrastructures, policies, and institutions within these spaces, that address all the “isms” and the violence caused by those isms. Company that is not critical of its own terms of existence can serve to perpetuate all the social and ecological violence that a critical planetary romanticism hopes to confront and diminish.

Note: This was presented at the AAR in Boston 2025 as part of a panel on “Ethics in the Anthropocene,” and comes from my forthcoming book, Critical Planetary Romanticism: Religious and Scientific Sources for a New Materialism(Columbia University Press 2026).

#

Whitney Bauman is Professor of Religious Studies at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami, FL. He is also co-founder and co-director of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, a non-profit based in Berlin, Germany that holds public discussions over social and ecological issues related to globalization and climate change. He is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship and a Humboldt Fellowship, and in 2022 won an award from FIU for Excellence in Research and Creative Activities. His publications include: Religion and Ecology: Developing a Planetary Ethic (Columbia University Press 2014), and co-authored with Kevin O’Brien, Environmental Ethics and Uncertainty: Tackling Wicked Problems (Routledge 2019); 3rd edition of Grounding Religion: A Fieldguide to the Study of Religion and Ecology, co-edited with Kevin O’Brien and Richard Bohannon, (Routledge 2023). He is also the co-editor with Karen Bray and Heather Eaton of Earthly Things: Immanence, New Materialisms, and Planetary Thinking (Fordham University Press 2023). His next monograph is entitled, Critical Planetary Romanticism: Religious and Scientific Sources for a New Materialism (Columbia University Press, forthcoming 2026).

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 3 December 2025.” The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

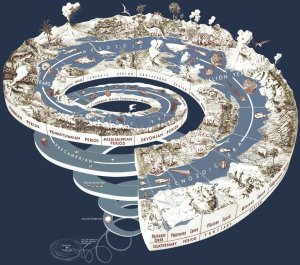

Image credits: “Geological Time Spiral.” Free download from Wikimedia Commons.